CBC padding oracle attack - cbc

The associated script, ciphertext, and PDF of the solution can be found in this repository:

Script, ciphertext, and PDFFor this challenge, we can see that this is a CBC padding oracle attack. Please note that according to PKCS#7, padding is done like this:

n = # of bytes to be padded

Block of plaintext to be encrypted = “{some_plaintext}\xn\xn…\xn” (i.e, \xn is repeated n times)

The length of the block in this case is 16 bytes. Thus, if the whole block was padded, the block of plaintext to be encrypted would be:

\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10 (i.e., \x10 16 times)

Also, there must be padding at the end of the plaintext for the encryption algorithm to recognize it as valid plaintext. Thus, if the bytes of the plaintext without padding are an exact multiple of 16, the last 16-bytes block of plaintext should be padding.

Furthermore, there is something called a padding oracle, which, when given a ciphertext, tells the user whether its decrypted plaintext has valid padding or not.

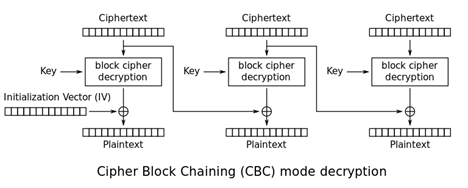

The decryption algorithm works in the following way:

Now, let’s say that c0 – c15 were the hex bytes of the second last block of ciphertext. Also, let’s say c16 – c31 were the hex bytes of the last block of ciphertext.

We can use the oracle to figure out i16 – i31 (i.e., the output after sending the last block of ciphertext through decryption (note: this is before XOR’ing it with the previous ciphertext)). The following math explains why this works:

Consider we want to solve for i31:

We know that if we can force the last byte of the plaintext to be 0x1, the oracle will give us a “yes” response. So, let’s try to force the last byte of the plaintext to be 0x1 by iterating through all values of a byte for the last byte of the second last block (let’s call this changed value c15’) and sending these messages to the oracle. Whatever message we get a yes for will mean we have forced the last byte of plaintext to be 0x1.

Consider the following math:

0x1 = c15’ ^ i31

Therefore, we can figure out i31 through the following:

i31 = 0x1 ^ c15’

Now, to solve for i30, we can do something similar. We can force the last 2 bytes of the plaintext to be 0x2. We already know what we need c15’ to be to get the last byte to be 0x2:

c15’ = i31 ^ 0x2

We can figure out what c14’ needs to be to get the second last byte to be 0x2 by iterating through all values of a byte for c14’ and sending these messages to the oracle. Whatever message we get a yes for will mean we have forced the second last byte of plaintext to be 0x2. Then, the same as before, we can solve for i30:

i30 = 0x2 ^ c14’

Now, if we rinse and repeat for every byte in the ciphertext, we can get the intermediate bytes for the entire ciphertext. The intermediate bytes of block n XOR’ed with the ciphertext bytes of block n-1 give us the plaintext for block n. We can repeat this for every block to get the plaintext and therefore, the flag. My python script cbc.py leaks the actual intermediate bytes, while my python script cbc_xor.py XOR’s the intermediate bytes with the ciphertext to get the plaintext. Thus, this challenge is solved.